Blog

Learn from our local travel experts and guides

GoWithGuide Posts

France

Paris to Giverny Day Trip: The Itinerary & Travel Tips You Need

Kuniaki T

Jul 07, 2025

Spain

What Is the Best Tour Company for Spain? Find the One That Fits You

Yui P

Jun 30, 2025

France

Paris Trip Planning: How to Plan the Perfect Visit for Your Pace & Style

Yui P

Jun 28, 2025

France

15 Best Places to Visit in France Besides Paris – Tour Guide’s Picks

Kuniaki T

Jun 27, 2025

France

What to Wear in Paris in the Fall: A Packing List for Style & Comfort

Courtney Cunningham

Jun 27, 2025

Spain

Barcelona With a Toddler: Everything You Need To Know To Enjoy Your Trip

Yui P

Jun 26, 2025

France

Paris to Bruges Day Trip Itinerary: All You Need To Know

Kuniaki T

Jun 24, 2025

France

Where to Stay in Paris for First-Time Visitors: Must Read

Kuniaki T

Jun 23, 2025

Guide's Posts

India

"Unlocking India's Hidden Treasures: Your Ultimate Guide to Booking Certified Tour Guides"

Asif K.

May 13, 2024

Japan

Miyama Kayabukino sato-Miyama Thatched Village

Tomoe S.

Oct 03, 2023

Japan

Summer Tea Ceremony (August 11, 2023)

Yoko T.

Jan 24, 2024

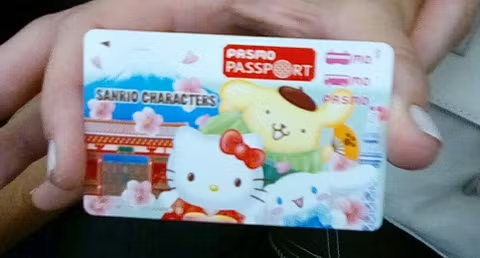

Japan

Transport In Tokyo: Getting A Welcome SUICA or Pasmo Passport Is Recommended

Yoko T.

Mar 21, 2024

Japan

Autumn Leaves Viewing in Tokyo

Kashima H.

Jul 27, 2023

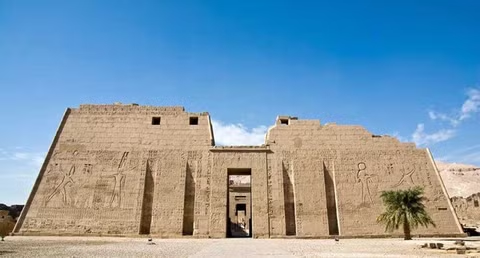

Egypt

Medinet Habu

Mahmoud O.

Jun 12, 2023

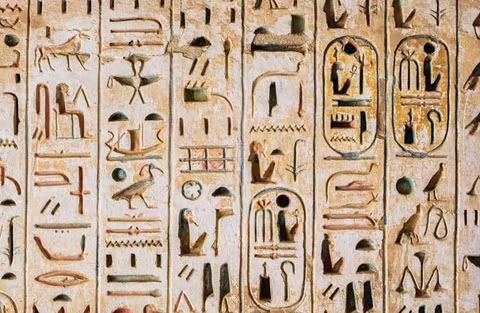

Egypt

Ancient Egyptian Language

Mahmoud O.

Jun 12, 2023

Japan

A trip from Aomori to Akita, driving along the coast of Japan Sea

Tomoe S.

Aug 17, 2023